Historical Fiction Research

How to Research for Historical Fiction

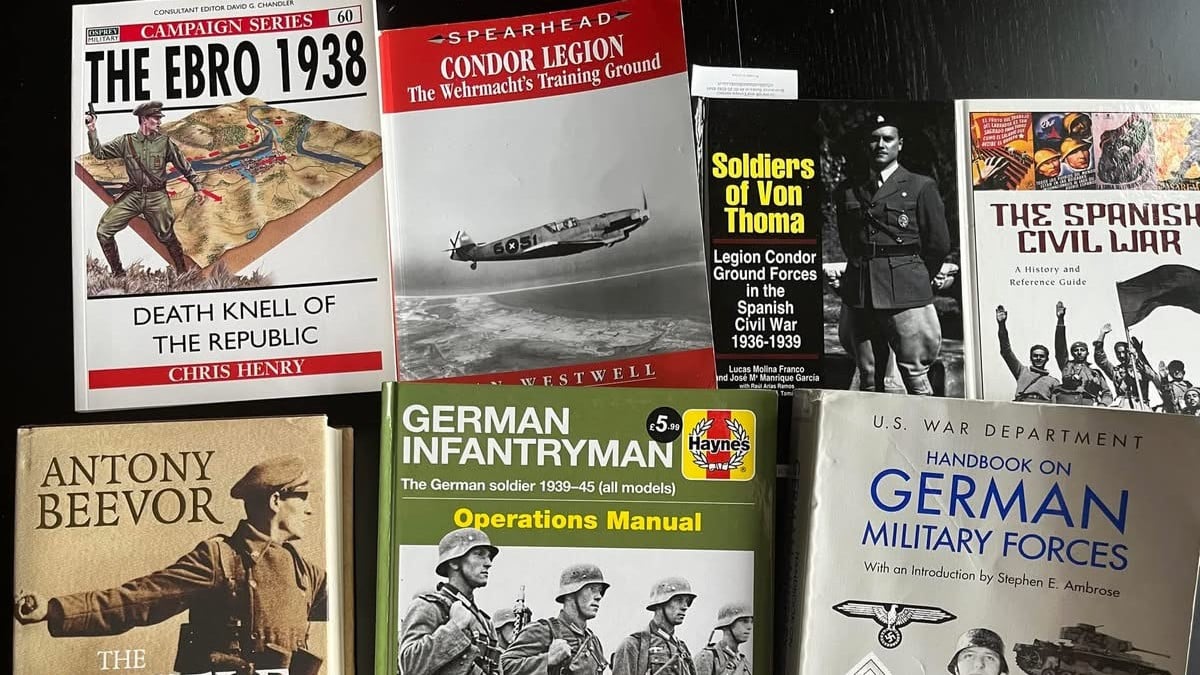

Research is the backbone of historical fiction. To make your story feel authentic, you need more than just imagination—you need context, detail, and a healthy skepticism of what’s “common knowledge.” Here are some approaches that can help:

1. Start with primary sources. Diaries, letters, memoirs, newspapers, and government documents give you the closest view of how people lived, spoke, and thought in the period you’re writing about. These sources often reveal small, vivid details—what soldiers ate, what civilians wore, or even the nicknames of key locations—that secondary sources might overlook or misrepresent.

2. Use secondary sources wisely. Histories, biographies, and scholarly works can provide valuable context, timelines, and analysis, but be aware that they sometimes repeat mistakes. For example, in researching my novel And the Devil Just Laughed, I found conflicting accounts of a hill called “The Pimple” (aka Hill 481, aka Puig d'Aliga, aka Cim de la Mort) during the Battle of the Ebro. Cross-checking sources was not help, and it wasn't until I actually visited the site that I realised the confusion lay in the fact there are TWO Hills 481! It transpired that several authors writing about the battle had not been there!

3. Visit the setting if possible. While not essential (but see previous note!), seeing a location in person can add depth to your writing. Walking the terrain, noticing the light, the smells, or the layout of a town, can spark details you might never find in a book. Even a brief visit can help you feel the place as your characters would have.

4. Pay attention to period-appropriate details. Language, clothing, tools, and daily routines all change over time. Avoid anachronisms—items we take for granted today might not have existed in your era. I make a point of using contemporary names for locations and checking that objects in my scenes were actually in use in 1939.

5. Mix media. Maps, photographs, film, museum collections, and oral histories can all enrich your understanding. Sometimes the most useful information is found in unexpected places—a painting, a travel guide, or even an old advertisement.

6. Question everything. Historical research often reveals contradictions. Historians disagree, sources misreport, and memories fade. Part of the writer’s job is to weigh evidence carefully and make choices that are both accurate and compelling for your story.

In the end, research is both a safety net and a springboard. It prevents glaring errors, but it also fuels your imagination, helping you create a world that feels real. Historical fiction works best when readers sense that the past has been treated with care—accurate enough to convince, detailed enough to immerse, and vivid enough to entertain.